El Niño… Say What?

January 31, 2016

In our everyday lives, we only encounter weather phenomena when they are present. For example, when the daily temperature is frigid for a prolonged period of time (as they were in the winter of 2014) the term “Polar Vortex” appeared. Take a look also at the term “Bombogenesis,” referring to the rapid drop in pressure of a storm. Lately however, a new term has emerged: “El Niño.” The boy.

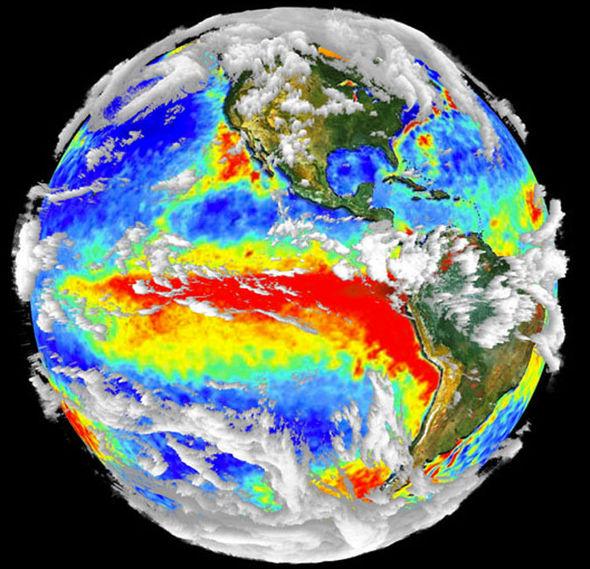

But what is an El Niño? Is it a storm? Is it a weird colored light in the sky? Neither, as it turns out. An El Niño, also known as the “warm phase” of the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), is the periodic warming of the waters in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. It occurs, on average, every two to seven years. Its counterpart is the “cool phase” of the ENSO, which is called La Niña. There are many indices that are used to measure the conditions for a potential El Niño and its strength, including sea-level pressure, sea surface temperature, and surface air temperature. One index, however, deserves special consideration: the Ocean Niño Index (ONI). The ONI measures the sea surface temperature of the central equatorial Pacific Ocean. Based on this, the Climate Prediction Center (CPC) defines an El Niño as when the central equatorial Pacific Ocean experiences sea surface temperatures of 0.5°C above average for at least three consecutive months.

During an El Niño, weather is affected not only in the Pacific Ocean, but also in the Atlantic. Warmer waters spread from the western to eastern Pacific Ocean, allowing stronger thunderstorms to move east since trade winds become weaker or reverse their direction. In addition, the west coast of North America typically receives increased levels of precipitation – a welcome sign for the drought-plagued California. Typically, the winter is milder in the Midwest, whereas the southern tier of the United States experiences a cooler winter with increased precipitation.

But, it’s not just winter that’s impacted. Hurricane season in the Atlantic Ocean is relatively quiet, as less storms form due to an increase in upper level winds varying greatly in direction and speed. On the other hand, the eastern Pacific Ocean sees more storms forming since the warm waters aid in tropical cyclone formation.

Previously, the strongest El Niño on record was in 1997, when the ONI measured sea surface temperatures to be a record 2.3°C above average. Since then, there have been a handful of weak to moderately strong El Niños. However, the El Niño that developed last year has matched that of 1997, with sea surface temperatures 2.3°C above normal. This El Niño has contributed to last year being the warmest on record, according to NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Now, how does climate change influence an El Niño? Human-caused climate change may be able to impact the strength of El Niños, but there is a lack of evidence to support this. According to the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), climate change and El Niño could act upon each other, possibly aiding the development of stronger storms. Yet, a study in 2013 performed by Kim Cobb of the Georgia Institute of Technology has shown that fluctuations in global temperatures have had no direct relationship with El Niños in terms of their strengths over the course of the past 7,000 years. This study did discover that El Niños in the past century have increased in strength. Another study, done by Wenju Cai and others in 2014, showed that strong El Niños will have an increase in frequency in the future because of climate change.

Simply put, as El Niños increase in strength, their impacts become more pronounced. For us, that could mean less snow and hurricanes in an El Niño season, but it definitely won’t prevent all storms.